If the definition of insanity is expecting different results when repeating something, I have an annual madness. Each spring I long for the freedom my children and I will enjoy when school ends. Summer arrives like an empty cargo ship docking on shore after being distantly visible for many months. Yet almost immediately, shipping containers of places to go, people to see and things to do fill the entire boat. Stop the longshoremen! I want to yell.

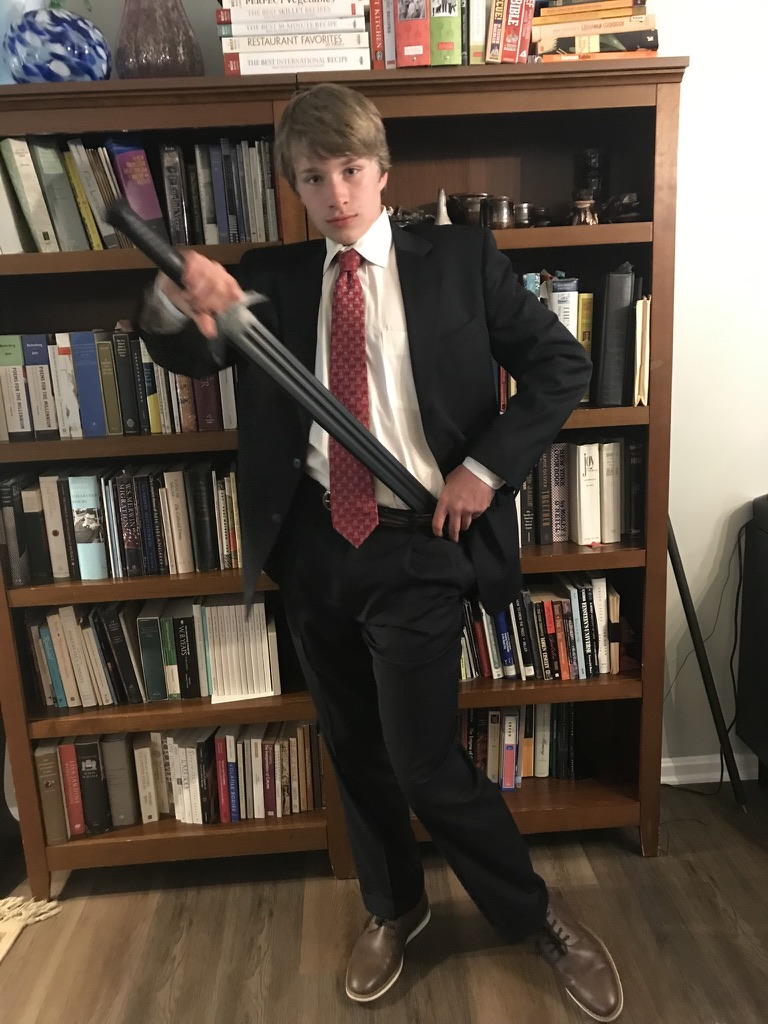

Since late June, I have not been home for more than three consecutive days as I have visited friends and family in faraway places. In mid-July, two adult-sized children, one tiny dog, all our camping gear and I filled every available inch of space in my small car. Spare shoes went under the seats, while in the back seat my daughter leaned on bedding stacked into a tower taller than her. My son’s size-12 feet were trapped on the car floor, surrounded by my computer bag, snacks, his sword and an intimidatingly large Nerf blaster.

I don’t consider myself a camping kind of person. I suppose that’s because, unlike my 28-year-old son, Hugo, I don’t spend months longing for the day I can load up the car, head to a camp ground and party like it’s 1899. And yet I’ve camped most years of my life. When I was a young child, my grandparents, Eagle Scout-level camping people, took me to parks near Chicago. They had all the gear, including canvas tents tall enough to stand in and wide enough to set up multiple cots. Later, after they’d retired to Arizona, they bought an Aristocrat mid-sized trailer camper. I cherish memories of comfortably camping with Grandma at remarkable state and national parks in the 1970s and ’80s, including multiple trips to the Grand Canyon and Lake Powell.

Beginning in the ’90s, I took my children every summer for over 15 years to Karme Choling Buddhist Meditation Center in Vermont for a nine-day family camp. The mountainside behind the center’s large building is dotted with semi-permanent tents set upon wooden platforms. Two adults and three children could sleep comfortably inside the tents on thick foam pads provided by the center. Served in a large dining tent, all meals were prepared and served with the help of the adult attendees. For several years, I arose early each day and made many gallons of coffee.

Camping at Karme Choling was lot like living in a college dorm. The tents, beds and meals were provided. Mothers and small children showered and dressed together in community bathrooms. It wasn’t as cushy as staying in a camper or cabin, but neither were we roughing it.

My children have also grown up spending a portion of their summers with family in Charlevoix, Michigan, just 50 miles south of the Mackinac Bridge. From 2020 to 2023, my youngest two kids and I stayed in a camper set up in the driveway of family for five weeks each summer. The outdoor day camp on Lake Michigan that my children attended provided some semblance of normalcy during COVID. But with the death their grandfather last fall, we no longer have family in Charlevoix.

Though our family is gone, the many things that make northern Michigan a summer delight remain, which gets us back to my packed-to-the-gills car. This year, we pitched camp at Young State Park. Tents have come a long way since the medieval-like structures my grandparents owned in the ’60s. My 15-year-old son, Leif, and I can set up our eight-person tent in less than 15 minutes. (Note: Unless the people sleeping in the tent are all 3 years old, divide the number a tent says it can sleep by two. A two-person tent sleeps but one adult, our eight-person tent is best for no more than four.)

While Leif has a thin camping pad under his sleeping bag, my 12-year-old daughter, Lyra, and I sleep on an air mattress. After a day of packing, driving eight hours and setting up camp, it was almost 10 when we collapsed in our tent.

“Hold still,” Leif said suddenly and came to investigate something next to my head. I thought it was perhaps a mosquito, but it was much worse. A leak in the mattress. I patched it with what I had – two Bandaids. It was a chilly 48 degrees when Lyra and I awoke the next morning with only two layers of plastic under our sleeping bag as the mattress had deflated much earlier. All three of us giggled.

Yes, camping takes me out of my comfort zone. Campground bathrooms are utilitarian community spaces usually a healthy trot away from the campsite. Keeping food fresh in a cooler is a messy, difficult preoccupation. Cooking on a fire pit or camp stove is doable, but again requires extra effort and then there’s the cleanup. Cleanliness standards are apt to slide.

And yet what trips are most memorable? The perfectly comfortable hotel room is easily forgettable. Some of the most amazing starry skies I’ve gazed up at have been on walks to camp bathrooms at 3 a.m. The drift to slumber in a tent, where children are all within arms’ reach, is often accompanied by soft chatter and laughter. Once home, that first shower, cooked meal and night on a firm mattress are savored unlike most. So those longshoremen loading adventures on the ships that are my summers? They are free to carry on.

This was first published in the Akron Beacon Journal on Sunday, August 3, 2025.