In his first month as mayor, Shammas Malik asked Akron Public Schools to prioritize launching a universal pre-K program. The district has wasted no time boosting its commitment to early learning.

Next fall, Akron schools will offer full-day programming for Akron children ages 4 and up.

Why is funding a public school program for preschoolers so important and what results can be expected? Luckily, numerous long-term studies of preschool programs exist, yielding an abundance of data supporting their many benefits, particularly for the most underserved children.

Head Start, a federal-to-local pre-school program, was launched in the 1960s as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” It wasn’t mandated, so not all school districts adopted it. However, nearly 60 years later, research on the first groups of Head Start students show the impactful, life-long and even multi-generational benefits of attending preschool.

According to a recent Brookings Institute report, when compared to their older siblings who were preschool age before Head Start existed, students who attended three years of Head Start were “3% more likely to finish high school, 8.5% more likely to attend college, and 39% more likely to finish college.”

The financial benefit, both to the people who attended Head Start and taxpayers, is also notable. Again from the Brookings Institute, “Female students were 32% less likely to live in poverty as adults, and male students saw a 42% decrease in the likelihood of receiving public assistance.”

Early programming is an investment with long-term payoffs — in other words, it is not politically expedient. Also, as children do not vote, politicians often cater less to their needs than they do citizens at the other end of the age spectrum, the elderly, who not only can vote, but reliably do in large numbers.

Before entering kindergarten, students who have attended preschool will have learned many educational building blocks — things like the alphabet, numbers, colors, shapes. They also gain exposure to vocabulary that may not exist at home.

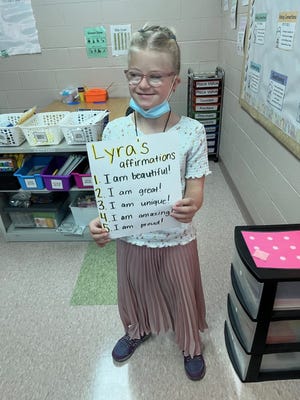

But equally important, students learn how to be in school. I’ve seen first-hand how consequential this is because my daughter, Lyra, who has Down syndrome, attended APS’s existing preschool programming, the Early Learning Program (ELP).

In Ohio, state support for children with disabilities is provided for the first three years of life through county developmental disability boards. Then, from ages three to 22, state support is delivered through the public schools, which is why Akron has an ELP.

Lyra attended Akron’s ELP for three years and when she began kindergarten, just after her sixth birthday, she could read, had basic math skills and knew her colors, shapes and more. She also knew how to behave in a classroom. Unfortunately, the same was not true for many of her more than 20 kindergarten classmates, most of whom were attending school for the first time. When the Akron Education Association negotiated a new contract with the district in 2022, student violence was a primary concern. Halfway through the 2022-2023 school year, kindergartners accounted for 24% of student “assaults” on staff and teachers.

Even with a fantastic kindergarten teacher, given the chaos of the classroom, Lyra did not learn the skills for first-grade readiness. We had her repeat kindergarten, this time with an aid to help her stay on task no matter what was happening in the classroom.

Children who are kindergarten ready when they start school are more likely to be first-grade ready at the end of the year. It’s reasonable to expect that the implementation of all-day pre-K means more Akron students will perform at grade-level. The accumulation of age-appropriate education, or the lack thereof, has exponential impact. Each year a student is promoted without the skills needed for their current grade level, the harder it becomes to acquire the skills of the next grade. But when a child has mastered grade-level curriculum, they are poised for success the next year.

The rate of return on the investment in preschool programming is eye-popping. For every dollar spent, communities gain $4 to $9 in return because students who\’ve attended pre-K are more likely to graduate and contribute to the economy and less likely to need public assistance or become incarcerated.

All-day kindergarten is a good step, but Akron still needs universal pre-k, which ensures any family that wants to enroll their preschool-aged child in a publicly funded program has the opportunity.

Foundations in Akron and Summit County should eagerly participate with the city and the school district to fully fund universal pre-K programming in because it is a direly needed game changer. The only problem with universal pre-K is that APS didn’t launch it many years ago.

This column was first published in the Akron Beacon Journal on Sunday, March 17, 2024.

For further reading of recent research on universal pre-K, see this NPR article.