In 2009, my three children and I drove to the Rocky Mountains for a family reunion. Though I hadn’t visited the Rockies since I’d lived in Wyoming two decades earlier, as we began our ascent into the mountains, they felt like an old friend whom time cannot estrange. Surrounded by flat prairies that emphasize the overwhelming enormity and ruggedness of the mountains, the range leaves an indelible impression.

But as the car reached higher altitudes, the landscape became horribly unfamiliar. Once verdant mountainsides covered in pine forests had turned a reddish color, not unlike that of a commonly used deck paint, which is also the color of pine needles after a tree has died. Though dead, the desiccated trees looked ashamed of their hideousness. To prevent wildfires, National Forest Service employees worked to clear cut the pine corpses, which were stacked in piles as large as barns. It looked to be a job with no end.

For the first time in my life, climate change wasn’t abstract reports of faraway glaciers melting, sea levels rising or storms growing stronger. Everywhere I looked for several days I saw the immediacy of climate change and its impact. The winters in Colorado are no longer cold enough to kill pine beetles and their numbers skyrocketed. Hungry beetles gorged until their food source, in this case pine trees, collapsed.

In 1990, Congress created the U.S. Global Change Research Program to “assist the Nation and the world to understand, assess, predict, and respond to human-induced and natural processes of global change.” Under this mandate, 15 federal agencies worked with scientists and citizens from all walks of life to create a first-of-its-kind National Nature Assessment (NNA1) of the “status, observed trends, and future projections of America’s lands, waters, wildlife, biodiversity, and ecosystems and the benefits they provide, including connections to the economy, public health, equity, climate mitigation and adaptation, and national security.”

This comprehensive assessment was nearing completion when its federal funding was pulled this January. Given the critical and urgent value of the NNA1–for how can we understand how our climate is changing if we do not take stock of where it is now–the non-federal authors of the assessment formed a new non-profit, United by Nature, sought and received non-governmental funding to complete their work.

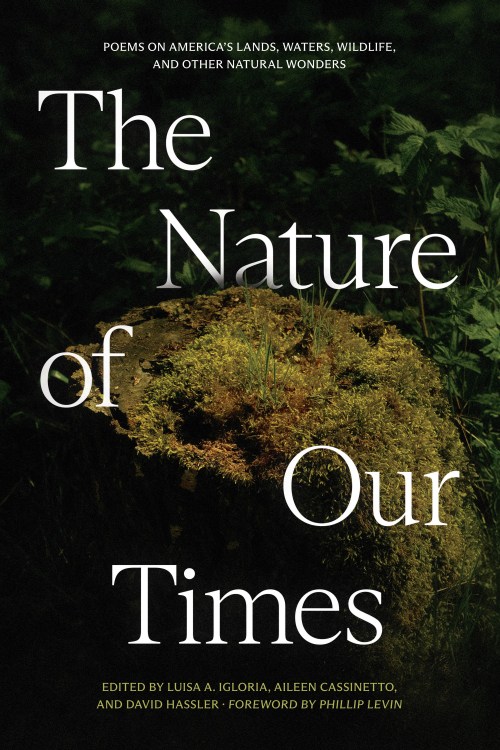

The NNA1 is scheduled to be released this fall as is “Nature of Our Times,” a poetry anthology companion to the NNA1. Many of the book’s poems reflect solastalgia, a word that means longing for a home that still exists but is rapidly changing before our eyes, just as the Rocky Mountains were when I visited 15 years ago.

I thought of that trip when reading Phil Levin’s foreword to “Nature of Our Times.” The director of United by Nature, Levin describes a knowledge that “resists spreadsheets and equations. It is the knowledge that comes from standing still. From watching a great blue heron glide above a salt marsh or listening to the layered calls of frogs at dusk. The lessons from such stillness are different than science, but no less true. And they remind us that the root of so much science is reverence.”

Kent State University’s Wick Poetry Center was a natural partner for the anthology. In 2017, poet Jane Hirshfield wanted a poetry presence at that year’s Earth Day March for Science on the Mall in Washington D.C. and collaborated with the Wick Poetry Center to create Poets for Science. Why poetry? When I asked Wick’s director David Hassler this question, he explained, “Poems focus receptivity to being aware and attending nature, as the late environmentalist and scholar Joanna Macy wrote, ‘whether as midwives to a new chapter of nature or hospice providers to a dying world, because presence and action are needed regardless.’ Poems offer us the possibility of emotionally shared experience that can spur people to interact beyond data and politics.”

Hirshfield puts it this way: “The microscope and the metaphor are both instruments of discovery.” Scientific data can be overwhelming, sometimes even obtuse, to the non-scientist. Whereas poetry, which speaks to emotions, can help communicate our understanding of science.

Poets for Science created an ongoing interactive website and put out a call for poems on how nature shapes our lives and how we can shape the future of nature. The website accepts submissions from anyone, not just published poets, and so far has received over 1,300 submissions, 210 of which were selected for the book and organized in four sections: Nature & Well-Being: Self & Community, Nature & Heritage, Nature, Risk & Change, Now & in the Future: Bright Spots.

This Thursday, Sept. 18, “Nature of Our Times” will be released. That evening at 7, there will be a poetry reading and discussion with Levin and the book’s co-editors at the Kent State Student Center Ballroom Balcony. The following day, Cleveland Public Library’s downtown branch will unveil more than two dozen banners with poems from the book coupled with nature photography.

Poetry won’t solve nature loss, but according to Levin, “The poet’s job is to speak what cannot be said in any other way. The scientist’s job is to seek the truth with rigor and openness. The public’s job—our job—is to listen, to learn, and to respond.”

This was first published in the Akron Beacon Journal on Sunday, September 14, 2025.